by Paula Mints

The PV industry is global, and its pricing function has a cultural basis. Particularly as it is dominated by China, without an understanding of China and its market motivations, it is impossible to understand why PV manufacturers today, all rational actors, willingly accept 15% or lower manufacturing margins when margins for like industries are higher.

Examples from other industries include: Coal 40% to 50%, Iron and Steel 20%, Construction ~30%, Appliances 30%, Aluminum 20%, Industrial Machinery and Components 40%, Aerospace 40% and Agriculture 8%.

In the PV industry the average margin is 8%. Congratulations PV, you are on par with agriculture.

Aside from significant government support, China’s pseudo-capitalists operate like free market capitalists and, as long as they do not run afoul of the central government as Suntech famously did in 2013, are free to succeed relatively margin-free. China’s PV manufacturing sector is less risk adverse than in other countries and more willing to move rapidly past historic PV industry norms such as, in some cases, pilot scale manufacturing. There are also fewer manufacturing

regulations.

Much has been written about the relationship of the US stock market to the rapid growth of China’s photovoltaic manufacturing sector. Suntech filed its IPO in 2005; Trina Solar (TSL) filed its IPO in 2006 while Yingli (YGEHY) and LDK (LDKYQ) filed their IPOs in 2007. It cannot be denied that the proceeds from the IPOs fueled rapid expansion for many of China’s PV manufacturers, but this is certainly not the entire story behind China’s PV manufacturing success.

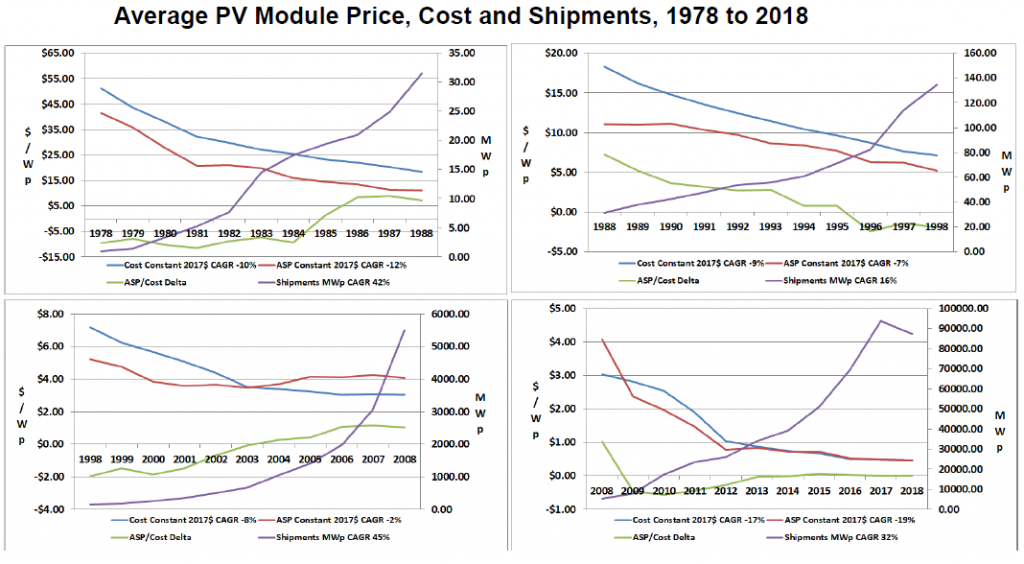

A Trip Down Pricing History Lane

In the early 2000s capacities to produce technology increased significantly while prices decreased significantly; for example, prices decreased by 42% in 2009 over the previous year, by 16% in 2010, by 23% in 2011 and by 45% in 2012. Unfortunately, these price decreases were misunderstood as a sign of economies of scale and it was widely assumed that the industry had reached grid parity. These assumptions were largely based the misunderstanding that price was closely correlated with cost and that price decreases represented progress.

During this period of strong activity, manufacturers in China entered with aggressive pricing strategies that rapidly drove PV manufacturers into a prolonged period of negative margins, company failures and consolidation.

In 2001 global shipments were 352-MWp and China’s photovoltaic manufacturers had <1% share. In the mid-2000s the market for solar deployment accelerated, driven by the feed-in-tariff incentive model. Between 2004 and 2009 accelerating demand for solar deployment met with a severe shortage of polysilicon starting material and therefore crystalline module product. Prices for modules increased and smaller markets outside of Europe had trouble sourcing module product. In 2004 China’s manufacturers had a 1% share of the global shipment total, 1.1-GWp. By 2007, China’s manufacturers had a 21% share of global shipments. By 2010 China’s manufacturers had a 38% share of global shipments.

How China’s manufacturers accomplished this feat has been and still is debated. On one hand the country’s manufacturers enjoy significant and generous incentives and subsidies from the central government as well as local governments. Initially labor was far cheaper in China than it was in other countries and other costs, such as electricity were also less expensive. The

country has had a vibrant shadow lending industry. China’s intricate avenues for borrowing money do not always intersect and are generally opaque to outside observers. Debt has always been a murky topic concerning China and its manufacturers expand, in some cases, using grey market debt (shadow lending).

China’s astounding and rapid success and domination of photovoltaic manufacturing also owes a lot to the market reform of Deng Xiaoping. Under Deng Xiaoping in the 1990s a new breed of businessperson came into being laying the groundwork for the country’s PV pioneers in the mid-2000s.

In 2018, the global industry finds itself in the midst of another price crash. The low prices are temporarily good for developers and installers and long term, very bad for manufacturers and quality.

Paula Mints is founder of SPV Market Research, a classic solar market research practice focused on gathering data through primary research and providing analyses of the global solar industry. You can find her on Twitter @PaulaMints1 and read her blog here.

This article was written for SPV Reaserch’s monthly newsletter, the Solar Flare, and is republished with permission.