Tom Konrad CFA

YieldCos buy and own clean energy projects with the intent of using the resulting cash flows to pay a high dividend to their investors.

Several such companies, often captive subsidiaries of listed project developers, have listed on U.S. markets since 2013. So far, YieldCos have been a win-win: The developers that list YieldCos have gained access to inexpensive capital, and income investors have gotten access to a new asset class paying stable and growing dividends.

So far, they have also gained from significant stock price appreciation. The seven U.S.-listed YieldCos are up between 21 percent for Abengoa Yield (ABY) and 136 percent for NRG Yield (NYLD) since they were listed.

However, some experts believe YieldCos are overpaying for projects. “We’ve seen them purchasing at prices we think don’t make sense,” said Chris Francis, the founder of Seven Waves Corporation.

Francis describes Seven Waves Corporation as a private YieldCo. Like its publicly traded cousins, Seven Waves invests in solar projects. The publicly traded YieldCos are his direct competitors, and their access to cheap capital “has made us adjust the prices” that Seven Waves pays for projects.

Seven Waves has to meet the return objective of its investors, and the competition from YieldCos has made it “a very slim business, with not much meat left on it.” It is still possible for Seven Waves to acquire projects. It has had to adapt to a much more difficult environment, but Francis expects to close on the purchase of a 76-megawatt solar farm in the next few weeks.

What they are paying

Francis, like most financial professionals, evaluates the value of a solar project using the metric internal rate of return. IRR gives an interest rate or yield, which allows a project with cash flows that vary over time to be compared to a simple-interest-bearing investment like a CD or a bond.

Not all public YieldCos announce their acquisitions, and none of the ones that do have disclosed the IRRs for the projects they are investing in. TerraForm Power’s recent announcement of its purchase of 23 megawatts of solar from Integrys is typical.

It says, “These plants are expected to generate average levered CAFD of approximately $5 million annually over the next 10 years. The equity consideration to be paid for the acquisition is $45 million. In addition, TerraForm Power will assume $10 million in project debt. This represents an expected levered cash-on-cash return of greater than 9%.”

“Levered cash-on-cash return” is a lot less useful than IRR, in the same way that “payback” is a less-than-ideal way to evaluate the value of an investment in solar for your home. Payback is just the inverse of cash-on-cash return. In this case, payback is 11 years ($55 million cost / $5 million CAFD, also equal to 1 divided by the cash-on-cash return). Both payback and cash-on-cash return fail to account for inflation, depreciation, project lifetime, or anything that happens after the payback period.

In the case of TerraForm’s announcement above, we are told, “The assets were placed into operation between 2008 and 2013, and are contracted under long-term power-purchase agreements (PPAs) with a variety of commercial and municipal entities having a weighted-average credit rating of Baa2. The contracts have a weighted average remaining life of 15 years.”

But the payback and cash-on-cash return would be the same if the projects had just been built and had PPAs that had a remaining life of 20 years or more, making them more valuable. Cash-on-cash return would also not change if the PPAs only had 10 years to run, and the solar farms were at the end of their useful lives.

Despite the weaknesses of the metrics cash-on-cash return or payback, these measures do not require assumptions about the long-term value of a wind or solar farm, and the truth is, no one really knows what that is. We don’t know what the electricity market will be like in 15 years.

Will TerraForm be able to sign new PPAs at that time, and at what price? Francis says that YieldCos seem to be “very aggressive” about their assumptions about future electricity prices. Historically, electricity prices typically have always risen, and YieldCos seem to be assuming that they will continue to do so. Francis, on the other hand, thinks that the large-scale deployment of renewable energy will cause prices to fall, at least in the middle of the day when solar is operational, and at times of strong wind in areas that have significant wind penetration.

He says he sees YieldCos getting 4 percent to 6 percent IRRs. That corresponds to the range of IRRs I compute from the 7 percent to 10 percent cash-on-cash returns from YieldCo announcements (see charts below). The TerraForm acquisition referenced above is one of the better ones; it has an IRR between 5 percent and 7 percent depending on the assumptions made about revenue after the PPAs expire.

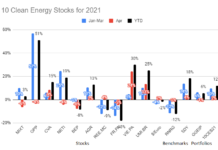

The following chart shows a compilation of cash-on-cash returns gathered from YieldCo announcements where they can be calculated. Note that these numbers are not strictly comparable from one YieldCo to the next because of slightly different assumptions about how to treat assumed debt and what expenses are deducted from the project’s expected cash flow.

TERP’s Integrys acquisition is shown at 11 percent, not the 9 percent cited in the press release, because I judged that removing the assumed debt from the purchase price made it more comparable to previous TERP announcements.

According to Francis, some unannounced acquisitions have even worse IRRs. One had an IRR of 1 percent when evaluated using Seven Waves’ assumptions. He thinks that such purchases could only be justified if the buyer assumes a 10 percent to 15 percent increase in electricity selling prices for the second PPA, with ongoing 2 percent annual price increases after that.

Such assumptions imply that utilities would be willing to pay far more for a PPA with an old solar farm than they would have to pay to construct a new one, given the widespread consensus that the price of new solar installations is likely to continue to fall, not rise. Francis observes that we have already seen some utilities trying to get out of PPAs in court. That does not bode well for their willingness to sign even more generous PPAs in the future.

Trends

Despite widespread talk that the market for clean energy projects is getting more competitive, I was not able to find a long-term trend of cash-on-cash returns over time. While some YieldCos such as TerraForm and Pattern Energy Group (PEGI) seem to be getting better returns than other YieldCos, most of the highest returns are on the smallest investments, as shown in the chart below. The labels and bubble sizes show the size of the purchase, not including assumed debt.

What we can see is that the pace of deals has been picking up. More of the deals shown in the chart closed in the first half of 2015 than in all of 2013 and 2014 combined.

Francis believes that thi

s level of frenetic deal-making may soon come to an end. He thinks that when the federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) falls at the end of 2016, it may lead to a short burst of deal-making as project developers leave the industry and sell off their existing farms. Some developers will continue to build farms, but at a more sedate pace, because it will be less lucrative without the ITC.

The effects on YieldCos

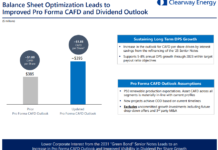

YieldCos can only raise dividends by acquiring more projects, or making the projects they have more productive. Both require cash to invest. Paying high prices (and getting low IRRs) for projects means that they have little or no money to invest after they pay their dividends.

So far, rising share prices and secondary stock offerings have provided the funds for these investments, but this will only work if investors’ giant appetite for YieldCo shares continues. That appetite for YieldCo shares depends on their expectations for continued dividend increases.

Anything that disrupts either investor demand or rising YieldCo dividends will feed back to disrupt the other in a vicious cycle. Stagnating dividends will attract fewer new investors, and fewer new investors will be able to fund fewer of the acquisitions the YieldCos need to keep raising their dividends.

In recent weeks, rising interest rates have begun to dampen investor demand for YieldCo shares. Will that or some later event like the ITC’s sunset trigger the vicious cycle? We will only know in hindsight.

As for Francis, rather than continuing to try to compete with YieldCos’ cheap stock market capital, he’s hoping that he can get access to some of his own by possibly taking Seven Waves public through a reverse merger with a listed company.

***

Tom Konrad is a financial analyst, freelance writer and portfolio manager specializing in renewable energy and energy efficiency. He’s also an editor at AltEnergyStocks.com. He will be an instructor at EUCI’s “The Rise of The YieldCo” workshop on July 30th and 31st. This article was first published on GreenTech Media and is reprinted with permission.

Disclosure: Tom Konrad and/or his clients own shares of Pattern Energy Group (PEGI) and TransAlta Renewables (TSX:RNW), and short positions in NRG Yield (NYLD).

Disclosure: Long

DISCLAIMER: Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. This article contains the current opinions of the author and such opinions are subject to change without notice. This article has been distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed.