Eamon Keane

Following the worst traffic jam in history this past August, Beijing has introduced significant curbs on cars. New car registrations will be slashed 70% to 240,000. Non-registered cars must have a permit and cannot travel at peak hours (7-9am and 5-8pm).

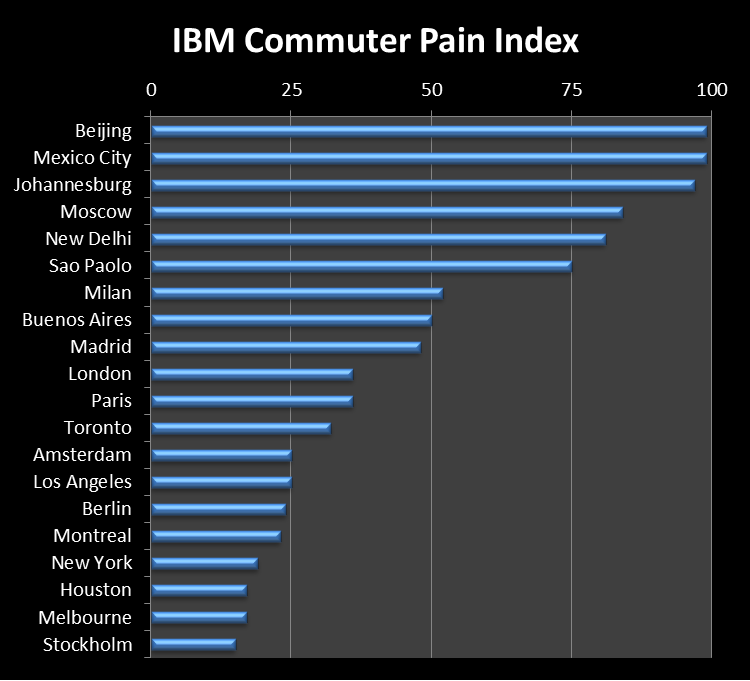

With 4.7m cars and a population of 22m, Beijing only has approximately 200 cars per 1,000 people. This is just half the level of cars in Mexico city with which Beijing is tied in IBM‘s “Commuter Pain Index“. If you think LA is bad, Beijing is 4 times worse:

When rumours of the restrictions on car sales surfaced a couple of months back, new car purchases spiked dramatically and fights broke out as punters vied for cars. For the 120m Chinese households mainly clustered in coastal cities earning over $5,000 (the level at which car ownership becomes affordable), having a car, aside from the personal freedom it affords, is a sign that you’ve made it. Banned from owning a car up until the 1980s, Chinese citizens now want some of that private car goodness. Sales increased 46% in 2009 and a further 35% this year, to reach 18m.

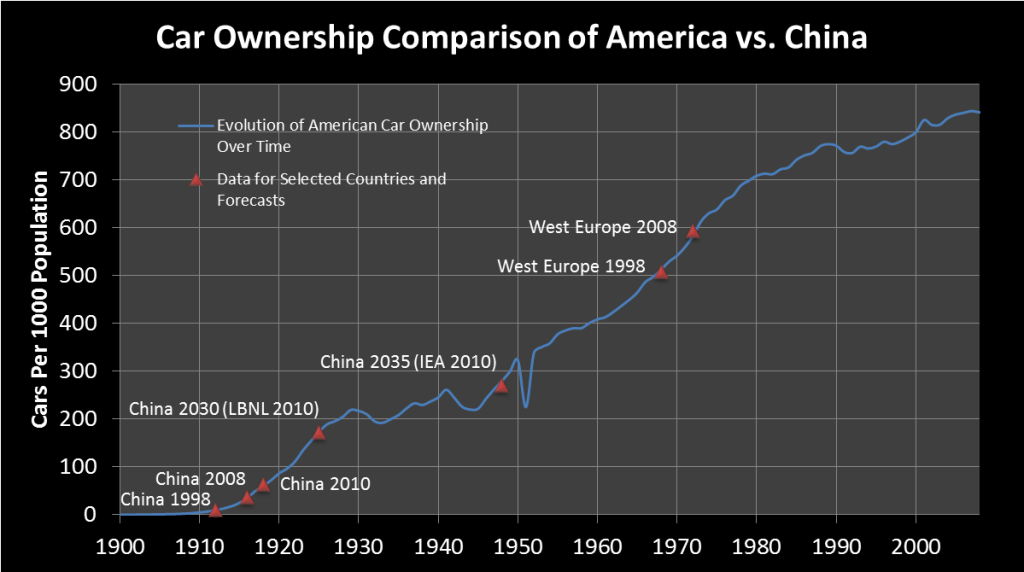

Many other cities such as Guangzhou, Shanghai and Shenzhen are snarled up also. Chronic traffic and smog are just two reasons why China must not follow the car centric American/OECD culture. The Chinese road network is almost saturated with cars. One strategy is to frantically expand it and hope for the best. Yet here is a timely opportunity to redefine mobility for the globe’s most populous country. The assumption in all energy forecasts is that Chinese car ownership continues to rise quickly:

The growth in Chinese passenger car sales is the single largest growth factor for global oil demand over the next 20 years. The IEA states “Holding all other factors equal, a 1% per year faster rate of growth in car ownership in China alone would result in around 95 million more cars on the road in 2035 and 0.8 mb/d of additional oil demand”.

There are some grounds for optimism. Several Chinese websites offer dynamic ridesharing and several cities have bus rapid tranist (BRT), a cheaper alternative to rail. The remarkable rise of electric 2 wheelers (E2W) in China, which occurred nowhere else, shows that things can be different. Chinese sales have soared from a few hundred in 1994 to around 22 million this year and may rise to 32 million by 2014. With around 120 million E2Ws in China, the Chinese are largely comfortable with electric drive. E2Ws took off in China for a couple of crucial reasons: (1) many cities curtailed gas mopeds due to air pollution, (2) E2Ws have a low total cost of ownership, (3) no licence was required and use of the cycle lane was permitted. E2Ws are subject to the 20/40 rule: max speed 20km/h, max weight 40kg. They’re still faster than Beijing traffic.

Innovative and cheap EVs, with a modular market structure similar to E2Ws are being built by Kandi (KNDI). They are a great way to cut pollution and all the better if they are used for ridesharing in cities. They also help the Chinese government meet its lofty goal of 1 million EVs by 2015.

With sufficiently strong direction from government further supporting car alternatives (while suppressing cars), a rising oil price, and a terrible driving experience, the Chinese may yet avert their covetous gaze from OECD style private car ownership. They may even teach the West a thing or two – E2Ws are beginning to take off in Europe with sales this year of around 1 million.

Disclosure: No Positions

Nice piece Eamon! The one number that surprises me is that 95 million new cars would only increase oil demand by 0.8 mmbd, or roughly 1 liter per vehicle. That seems low to me and might merit a double check.

A while back Pike forecast up to 80 million E2Ws a year by 2016 and my sense is that they’ll be far more popular in Europe and the US than even Pike predicts because the cost-performance equation is so favorable. I also like the KNDI model and am glad to see you don’t disagree,

Good due diligence, 0.8mb/d did strike me as low also, however I didn’t double check. Perhaps I am giving the IEA too much credit.

If we assume 16,000km per year, that’s 44km/day. 44km/day * 95m = 4,200m km/day. The usual fuel efficiency gauge is litres/100km, so that’s 42m 100km/day. 0.8mb/d equates to 128m litres/d. The IEA are thus assuming around 3 l/100km (128/42). This is an aggressive efficiency goal (Prius = 4.7 l/100km), so perhaps they are assuming lower per vehicle travel. If they are assuming 10,000km per vehicle, then a more reasonable 4.8 l/100km is the result.

On E2Ws, I read your previous articles on them and did look at the Pike forecast. They coyly didn’t explicitly state Chinese sales, but I think you’re correct if you read between the lines. It might be worth dropping them an email to see if they really are forecasting 80m E2Ws! The other forecast I linked to is more subdued.

The cost per mile of E2Ws is half the cost of a gas moped and a third the cost of a small car (slide 16 of this pdf: http://www.jonathanweinert.com/presentations/E2W-CAFCP.pdf). And the cost gap is only going to increase. It’s a nice lever to have if a family is looking to cut down on costs!

Just a few comments. It is not all of China’s road network that is “almost saturated” but rather most city networks and also most of the main roads in the proximity of major urban centres. Of course, these areas are also where most cars are located. However, there are still new inter-city highways out there with long open stretches if you are prepared to go north and west!

This is not to detract from your main point that most Chinese cities are now clogged with traffic from early in the morning to late at night. I am not sure that building more and more ring roads and cross routes is the answer. Better driver education would be my starting point!

The growth of China’s e-bike market has been amazing with sales growth strong again in 2010 after a few weaker years. However, many of the models on sale today do not meet the 20/40 rule being both faster and heavier than, technically, is allowed. Fear that the rules would be enforced more stringently was probably a factor in the slower sales growth observed in 2008 and 2009. What is not clear is how the market would react if rules reclassifying faster and heavier e-scooters as electric motorcycles were introduced. Riders of these e-scooters would then need a license and insurance and would not be permitted to share the bicycle lanes.

I think that the Pike forecast for e-bike sales is very inflated and may flow from a significant over-estimate of recent/current e-bike production and sales in China.

Good points Huw. Better traffic signs and more experienced drivers will surely ameliorate the situation to an extent.

You seem to be on the ground in China. Would you view this as a teething problem on the way to 500 cars per 1,000 or do you think Chinese car ownership will end up structurally lower? It seems likely that urban sprawl and satelite cities could accommodate more cars if that was the chosen policy option.